|

|

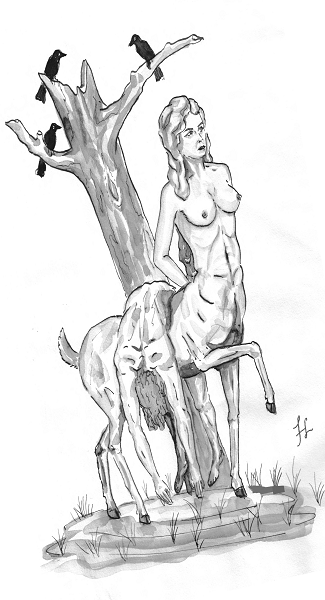

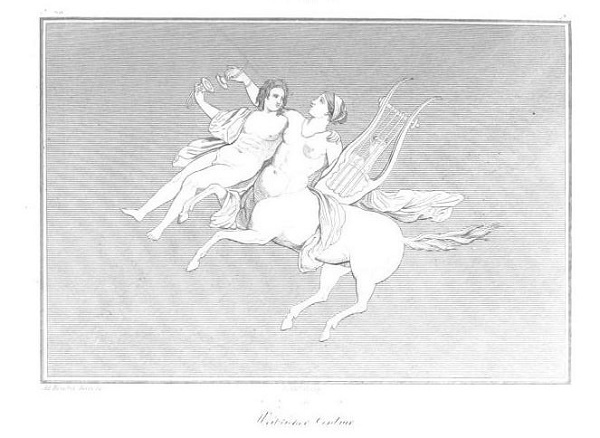

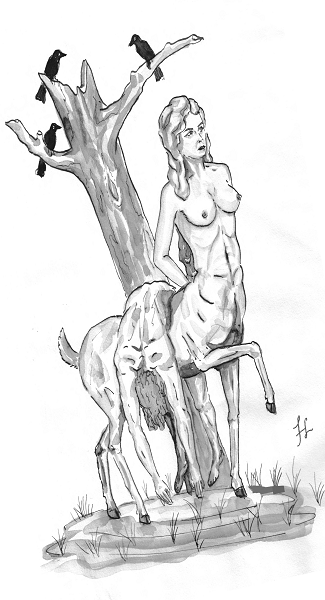

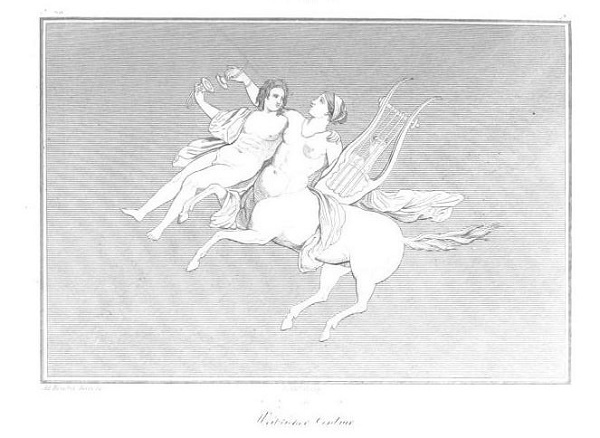

dainefemme: Fallow Doe of The Three Ravens Ballad

|

"To render 'fallow doe' literally presents three problems incapable of

solution: 1) How does the doe get past the knight's hounds?; 2) How does

the doe manage to "lift up his bloudy hed"?; 3) How does the doe manage

to fill the grave (if we assume it already dug)?

. . .

However, if we take 'fallow doe' as a metaphor for a woman

two new problems arise: 1) What is the significance of the epithet?; 2)

The tasks of getting the knight on her back and carrying him to a grave

require a strength which is inconguous with her attributes of tenderness

and loving concern. These problems strongly suggest the need of some

third alternative, and one is readily available; viz, this "fallow doe"

is a centaur-like woman, or to coin a word, a dainefemme(deerwoman),

presumably possessing nymph-like qualities." From The Three Ravens Explicated. |

The Three Ravens Lyrics (pdf)

The Three Ravens Lyrics (html)

The Three Ravens Explicated

(pdf image) also

here

1911

Encyclopedia Britannicaca

Hrolfs saga Kraka

Herculanum et Pompéi

Teutonic Mythology (Vol I, pp 430 - 433, wood-wives)

The Three Ravens Explicated (html/docx) and here

The Three Ravens - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Facts on File companion to British poetry before 1600

The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature p. 719

From

https://www.mustrad.org.uk/letters.htm

Re: The Three Ravens article

|

I'm pleased my article, some 55+ years

since publication, maintains interest.

The author

responds to: Thomas Ravenscroft and The Three Ravens: A Ballad Under the

Microscope by Arthur Knevett

Counter

argument is a good thing. The argument that 'the monastery of Derry

escaped the worst effects of ... [the Viking] raids' is not a [an effective]

counter argument against 'the Scandinavians plundered the city, and it is said

to have been burned down at least seven times before 1200; it thus is a site of

many battles.' The modern day Encyclopedia Britannica

[https://www.britannica.com] states 'the settlement was destroyed by Norse

invaders, who reportedly burned it down seven times before 1200,' so this is not

merely 'Chatman's contention.' Further, the assertion that the monastery

escaped the worst effects is beside the point or at least its import is not

explained.

The claim that

Derry was 'a small settlement, not a city' is of no weight, even if true.

The impact of any import is not explicit in the analysis of locale.

One is hard

pressed as to what to make of the remarks regarding Derry and Dorie when the

explication by Chatman is that the ballad (as we have it) is 'of Irish

derivation.' Whatever problem this represents is not explained in the

critique. For example, Knevett writes: 'The Ballad also migrated to

America and Arthur Kyle Davis Jr writes that; 'The American texts, ... are far

removed from the British versions.' Substantial variation in versions can

be observed.

Knevett seems

to complain about Chatman 'making use of grammar;' using grammar seems

reasonable for analysis of language artifacts, so I'm not clear on what the

argument is here.

The OED, as

referenced in the explication, confirms the description of the use of 'hay.'

Knevett's referring to the phrase 'to make hay of' is inexplicable. See

also: The Protestant Whore: Courtesan Narrative and Religious Controversy in

England, 1680-1750, approx. p.127 ('to make hay,' ... and this is the OED

again, 'to make confusion'. [https://tinyurl.com/u8qca8o]

Tracing the

history of written documents combined with historical linguistic information can

be useful for analysis of what is recorded of the products of oral tradition;

however, their undocumented pre-history can only be addressed with informed

speculation and analysis.

In conclusion,

we have seen that the most effective understanding of 'fallow doe' is the notion

of the dainefemme, the refrain is a meaningful and functioning element of

the ballad. The song is probably Irish in its origins, (the notion of the dainefemme is

probably the result of Scandinavian contact), the ballad makes use of ideas

which strongly suggest it originated long before 1611, the ballad is probably a

'war-song', and The Three Ravens expresses a sense of possible victory

over fate and death. All the elements of this ballad coalesce to produce a

tense, subtle, terse, and complex verbal icon. |